In my work across capability frameworks, learning systems, and workforce design, knowledge is one of the most frequently referenced — and most casually assumed — concepts. It sits quietly inside skills models, competency frameworks, and development pathways, rarely questioned but constantly relied upon.

What I consistently see is this: organisations invest heavily in knowledge acquisition and are surprised when performance doesn’t shift. That gap isn’t caused by poor learning — it’s caused by misunderstanding what knowledge actually does in a workforce system.

This article clarifies how knowledge is defined, why it is so often conflated with other constructs, and where it genuinely adds value.

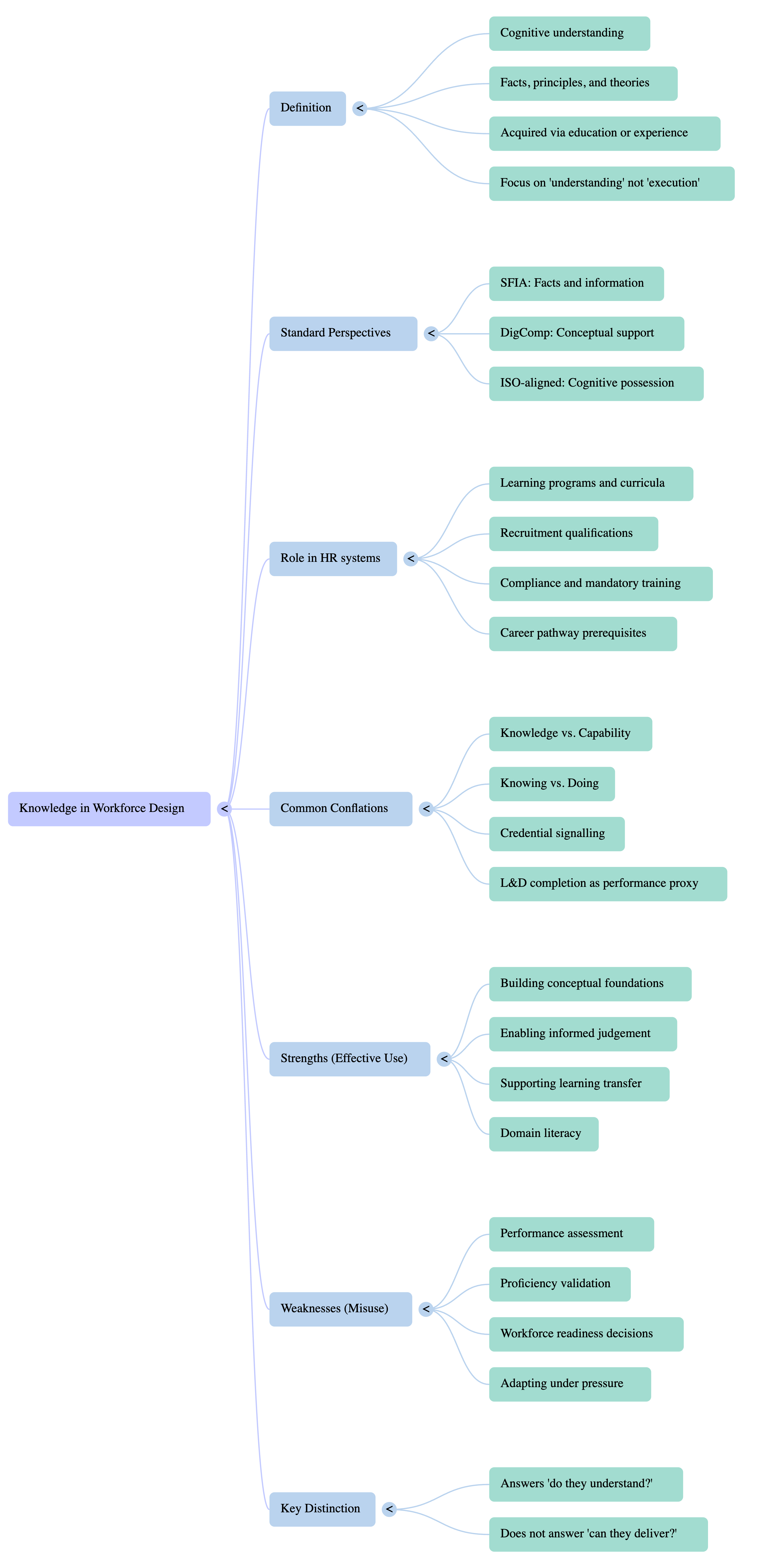

How Knowledge Is Commonly Defined

When we step away from practice and look at authoritative sources, definitions of knowledge are remarkably consistent.

The SFIA Foundation defines knowledge as facts and information acquired through education or experience, emphasising conceptual understanding rather than action. Similarly, DigComp 3.0 describes knowledge as facts, concepts, ideas and theories that support understanding of a subject area. Across ISO-aligned literature, knowledge is treated as cognitive possession — something a person can hold without necessarily applying.

From what I see, the standards are clear: knowledge is about understanding, not execution.

What the Dictionary Gets Right — and What It Misses

Most dictionary definitions describe knowledge as information or understanding gained through experience or education. That framing isn’t wrong, but in organisational settings it’s incomplete.

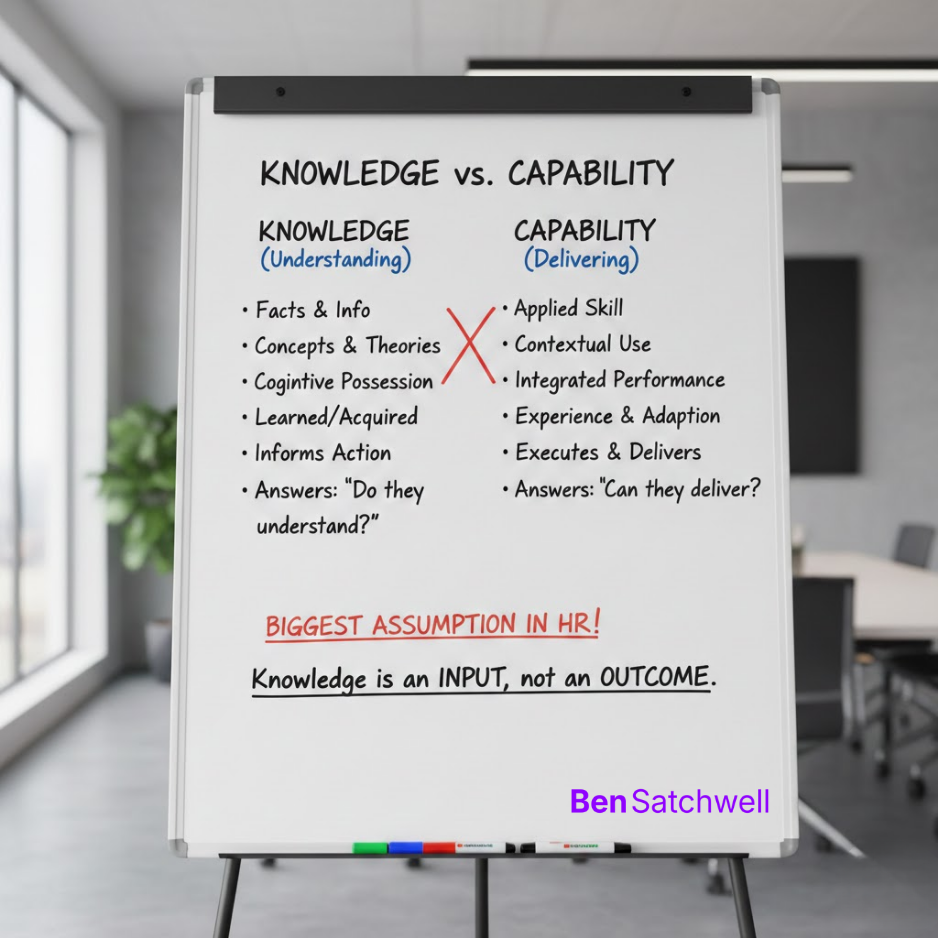

It gets two things right. First, knowledge is cognitive. Second, it can exist independently of action.

What it misses — and what causes problems in HR — is that knowledge does not imply readiness. It says nothing about whether someone can apply that understanding under pressure, adapt it to context, or integrate it with other demands.

In practice, I see organisations assume that knowing automatically translates to doing. It rarely does.

Why Knowledge Gets So Heavily Conflated in HR

From experience, knowledge is not misused because people don’t understand it. It’s misused because of how HR systems evolved.

A few recurring patterns show up again and again:

- Learning-centric histories: HR and L&D functions grew up measuring participation and completion. Knowledge became the default proxy for effectiveness.

- Credential signalling: Qualifications and certifications are treated as evidence of capability, even when they primarily signal exposure to content.

- System constraints: Learning platforms are far better at tracking knowledge acquisition than applied skill or performance evidence.

- Everyday language shortcuts: “They know how to do it” is used interchangeably with “they can do it”, even though those are fundamentally different claims.

None of this is malicious — but it is structurally reinforced.

The Problem Knowledge Was Originally Designed to Solve

At its core, knowledge exists to solve understanding.

In my work, knowledge plays its strongest role when it:

- builds conceptual foundations,

- enables informed judgement,

- supports learning transfer,

- helps people recognise what to do and why.

Knowledge answers a very specific question:

Does this person understand the domain they’re operating in?

It does not answer whether they can execute, adapt, or deliver outcomes. Those are downstream concerns.

How Knowledge Is Used in the HR Profession Today

Across organisations I work with, knowledge shows up predictably:

- In learning programs and curricula

- As qualification requirements in recruitment

- In compliance and mandatory training

- As prerequisites in career pathways

This works well in regulated or safety-critical environments, early-career development, and situations where baseline literacy genuinely matters.

It breaks down when course completion is treated as performance evidence, or when learning volume is mistaken for development progress. I regularly see organisations with highly trained workforces that still struggle to execute consistently.

A Clear, Practical Definition of Knowledge (My Position)

From both the standards and practical application, this is the definition I work with:

Knowledge is the cognitive understanding of facts, principles, concepts, and theories acquired through learning or experience.

It informs action and enables reasoning, but it does not constitute skill, competence, or capability on its own.

Knowledge answers “do they understand?”

It does not answer “can they deliver?”

.png)

What This Definition Supports — and What It Doesn’t

Used properly, knowledge supports:

- foundational learning and induction,

- accreditation and qualification requirements,

- domain literacy,

- better judgement and decision-making.

It is poorly suited for:

- performance assessment,

- proficiency validation,

- advanced development planning,

- workforce readiness decisions.

When knowledge is treated as an outcome rather than an input, organisations confuse education with effectiveness.

Why Getting This Right Actually Matters

Knowledge is essential — but it is only the beginning. In my experience, when HR systems reward accumulation of knowledge rather than integration and application, they create a false sense of progress.

Used well, knowledge accelerates learning and sharpens judgement. Used lazily, it becomes theatre.

Clarity here isn’t academic.

It’s the difference between learning more and performing better.